We departed the USA on March 15, 2003. Team Everest ’03 members departed from Austin and various cities across the US for the long journey to Nepal’s bustling capital city, Kathmandu. TE ’03 / CTD project director Dennis Borel was at the Austin airport, along with dozens of supporters, to see the team off. Dennis said, “Today is a tribute to every team member making this journey of profound importance to raise public awareness of the potential of people with disabilities.” Dennis’s words were prophetic, but in ways none of us could imagine.

We left Austin on our 36 hour flight via L.A, Taipei, and Bangkok, to our ultimate destination Kathmandu, Nepal (elevation 4,264ft). After several days in Kathmandu we took an early morning flight by chartered Twin Otter airplane to Lukla (9,184ft), the trail head into the Khumbu region. Several seats were removed from the airplanes to allow those of us in wheelchairs in stay in our chairs during the flight. At each airport it was a heartbreaker watching Mark Ezell try to wheel around in his purpose built wheelchair. It was designed for rough terrain but it was malfunctioning even on flat surfaces. We hoped it wouldn’t be a harbinger of things to come. Little did we know. Secretly, I was glad it didn’t happen to me.

When we got to Lukla, Rilely Woods and Matt Standridge wanted to have a look around. The Sherpa wanted to help but Matt and Riley insisted on making their own way. In the adjacent photo, Matt got out of his chair and scooted down the steps. Riley took the chairs apart and handed parts down to Matt who re-assembled the chairs. They made their way around town then back up the steps. Because their bodies were not yet acclimatized to the elevation, they paid dearly for it the next morning.

While Matt and Riley burned off some energy, I was getting re-acquainted with Tsering Sherpa (on left). I met Tsering in ’92 on my first trip to Nepal. He lead us (me and my friends from Kent State) on the Annapurna Circuit, a popular trek in Nepal. Back then he amazed me with his situational awareness. I was very pleased to see him on our TE ’03 expedition. Back then, I was carried, as I was now, in a modified bamboo basket (called a doko) by a group of porters led by Tsering Sherpa. Tse ring Sherpa uses his ethnic group’s name for his last name, as do all Sherpa people who live in the Khumbu and Solu regions near Everest.

The Sherpa amazed us all. Even though I was acquainted with the Sherpa from my trip to Nepal 10 years earlier, they still amazed me each and everyday. The Sherpa are of small stature compared to us. They averaged perhaps 5 1/2 feet tall and no more than 120 pounds soaking wet. Yet they could carry loads twice their weight over mountainous terrain at high elevations where the air is thin. In the picture on the right, a Sherpa carries Barry in his wheelchair, a load of well over 240 pounds.

We were sure to attract attention wherever we went. Not surprisingly, many Nepalese have never seen a person with a severe disability, especially at this elevation. When we were carried in dokos we were often separated from our chairs. I wondered if the villagers knew we were disabled or just thought we were lazy. Not having seen the wheelchairs, how could they think differently? If they had seen the wheelchairs, what did they think?

Progress If geographic milestones are any measure of progress then our progress was undeniable. We trekked from Lukla to Phakding along the Dudh Kosi (“Milk River”) and crossing suspension bridges over the river. Then on to Monjo (elav. 9,300 ft). We weren’t without our disappointments though. The guys in chairs wanted to wheel themselves. The terrain, however, wasn’t very accommodating. There were very few areas flat enough where someone could roll around. I too, was dismayed.

I felt a kindred relationship with the guys in chairs. However, since I couldn’t wheel myself, I was relegated to the ranks of luggage and was carried everywhere. I soon found myself ahead of the pack. Though being out front had it’s perks, I missed all the action elsewhere on the trail.

The tour of the forts built our appetite for the island’s comida criolla (traditional Puerto Rican cuisine). While roaming Old San Juan we found Restaurante El Jibarito. The food was great and Sangria even better. Afterwards, we went to Castillo San Felipe del Morro but it was about to close.

The next day, we trekked into Sagarmatha (Everest) National Park to Sherpa capitol Namche Bazaar (11,283ft).

Shortly thereafter we trekked to Lo Sasa (11,150ft) village and along a relatively level trail to Tengboche (12,694ft, the spiritual center of the Khumbu. Trek on to Deboche (12,300ft).

This is a picture of me and my brother Robert. I always stayed bundled up, often times more than what was warranted. My main fear was getting some sort of respiratory virus. I grew up in Cleveland, Ohio where the winters can be rather brutal. I was afraid Everest would be worse. As it turns out, my fears were unfounded, the weather on Everest was milder than any winter in Cleveland.

When my brother Robert past away June 4, 2007, I was naturally very upset and sad. But, 9 weeks later we got the autopsy report and found that he died due to prescription drugs, I was outraged as this news meant his death was preventable and indeed, would have been prevented if someone, either Robert or his doctor or pharmacist or “somebody” was more careful. I was looking for somebody to blame.

After I calmed down, I decided to look for a life lesson. I finally found it. I think Robert’s death can serve us all by reminding us that life is unpredictable and none of us know when our time will come. The best we can do is live everyday to its fullest.

Everyday was another blessing to enjoy the incredible beauty of the surrounding mountains and the camaraderie of fellow adventurers. Tents were comfortable enough. On occasion we would happen upon a lodge where, to my great joy and the joy of others around me, I was able to get a shower. It was a cold one though as heating fuel, like every commodity on the mountain, was at a premium. On the trail, evening meals were served in tents as seen below. Breakfast was served in the open.

At the beginning of the third week we trekked to Pangboche (12,660ft) and Dengboche (14,465ft), villages that seemed dwarfed by the surrounding peaks; the world’s 4th highest mountain Lhotse (27,890ft) & Ama Dablam (22,493ft). We made a day hike to small summer settlement Chukkung (15,514ft). We rested and acclimatized in Dengboche.

After acclimatizing, we trekked to Tuglar (15,150ft) & Lobuche (16,170ft) The landscape was now quite stark and reminded me of a desert. We saw numerous memorials to lost climbers. Most memorials were piles of stone on top of which were placed prayer flags and occasionally pictures of fallen climbers. These monoliths also served to remind the rest of us of our mortality. As with many extreme athletes, I have my own sense of mortality and have no fear of death. I don’t have a death wish though, I have a live wish. All of us will eventually die but not all of us truly live.

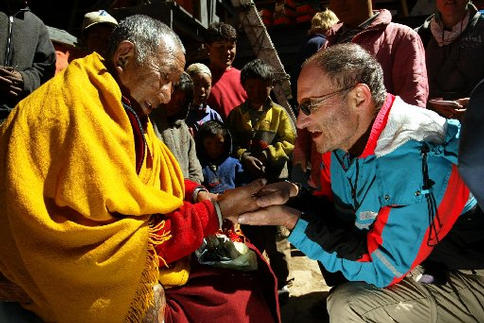

All along the trail we stopped to be blessed by Buddhist monks. Vince, a Team Everest member and man of the cloth, took the opportunity to also bless the monk. In August of 2008, Vince, who overcame cancer, then decided to place a bible at the summit of the tallest peak on each continent, died after scaling the Matterhorn in Switzerland. Pastor Vince Bousselaire and several partners were descending from the east side of the Swiss mountain when a storm moved in. Bousselaire and Carolyn Randall fell — both died. We mourn his passing.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter where we’ve been or what we did; it’s what we have become as a result of our endeavors.

We trekked along Khumbu Glacier moraine to Gorak Shep (16,925ft), a group of herders’ huts. It was a challenging ascent which rewarded us with a 360° panoramic view of Himalayan peaks.

It turns out Gorek Shep was my Achilles’ Heel. We weren’t in Gorek Shep long before I realized something was wrong. I just didn’t know what. I soon took ill. At first I thought it was from the altitude. But instead, I was overwhelmed by another force of nature – my own body. It was shutting down. It was as if I was having an “out of chair” experience. I knew my body was failing me but why? Thinking it was the altitude, I took a dose of medication that allows blood cells to absorb more oxygen. I laid down and hoped the prone position would help. I started bleeding through my nose and mouth. My brother summoned Janis, our team doctor. I lapsed in and out of consciousness. I don’t even remember the above picture. Sometime in the early morning hours I remember Janis telling me he was sending me back to Kathmandu. I saw something in his eyes I had never seen before. It wasn’t fear but something awful close to it. Since Day 1, Janis made it clear he was there to help. It was also clear his word was final. An appeal to a higher power would only be possible with the intervention of Providence. That was not likely. Only a fool would argue under those circumstances anyway. I knew Janis had no recourse and that going back was the ONLY choice. He told me I probably had a twisted bowel and would have to be hospitalized. If symptoms didn’t improve soon, I would need surgery.

When Janis told me he was sending me back to Kathmandu he asked if I could live with that. You would have to know Janis to understand the nature of that question. It got to the very essence of our being on the mountain. Everyone had their own motivation for being there. For some, it was the lure of adventure, others had something to prove – perhaps to themselves, perhaps to others. There were as many reasons as there were people. Dinesh and I didn’t want to go to Everest, we NEEDED to go to Everest. If others found our story inspirational then I was gratified. But that’s not why I was there. I have traveled on six continents, as Jim Croce would sing, “searching all the time for something that I never lost or left behind.”

I’ve engaged in many extreme sports ranging from sky diving to scuba diving. Not because I wanted to, I needed to. Janis knew I had my own reason to be on Everest and wanted to know if my soul was at rest, if I accomplished my own goals. I was very disappointed I would have to turn back only a few hours from our destination – base camp. I failed in my attempt but was satisfied I had tried my best.

I brought Jose and my brother Robert with me as my attendants. Gary looked at the 3 of us and said, “One of you is going to have to go down with Gene.” Robert volunteered. I knew he was disappointed he would not make it to base camp but it takes more than disappointment to break the bonds of blood. We said a few tearful good-byes, gathered our goods and headed out. A rescue helicopter couldn’t reach us at our altitude so I was carried down to a lower altitude. The doc took the lead and started pulling me, along with several Sherpa. Our decent would be much easier for 2 facts. One, we were working with rather than against gravity. Also, we would not need to take time to acclimatize our bodies to the altitude. Still, nothing on Everest is ever easy, with the exception of forging life long bonds with people that become closer than family. For Janis and myself, we shared an experience we’ll never forget but have no desire to remember.

Janis gives my brother Robert last minute instructions. At this elevation the helicopter can only take one of us at a time. It took me first to a lower elevation and dropped me in some field. Then he went back for Robert. It was the doctors’ job to keep us physically healthy, but on this type of adventure he saw to our mental health as well. In fact, we all looked after each other. We took care of each other. NOTE: Robert passed away June 4, 2007.

The rest of the Team trekked to Everest base camp (17,388ft); set up camp, rested, then had time to explore. The following day the Sherpa set up rigging for the Team to climb the Kumbu Ice Falls, a dangerous but beautiful area.

Having accomplished their goal, the Team departed base camp; descended to Gorak Shep, then Lobuche & Pheriche. From Pheriche, they took a chartered helicopter back to Kathmandu and eventually flights back to the US.

Reflections

I did not want to go to Everest, I needed to. I’m an Argonaut, an explorer, I could not deny my destiny. Having been there once, I would not go back, I don’t feel the need. My curiosity has been satisfied.

There are many reasons why one would want to go to Everest. The most common reason is ego. One Sherpa died during our expedition. That is a price too high to pay for one’s ego. In addition, my Canadian friend Chris was afflicted with pulmonary respiratory and cardiac edema. We could have lost him and the world would have been a poorer place for it.

If you go to Everest be clear on your motivation and be clear what you are risking, not only your own health and welfare but that of the Sherpa as well.